A 'Brief' History of Game AI Up To AlphaGo, Part 3

On the two-decade story of how two revolutionary ideas were combined to make AlphaGo |

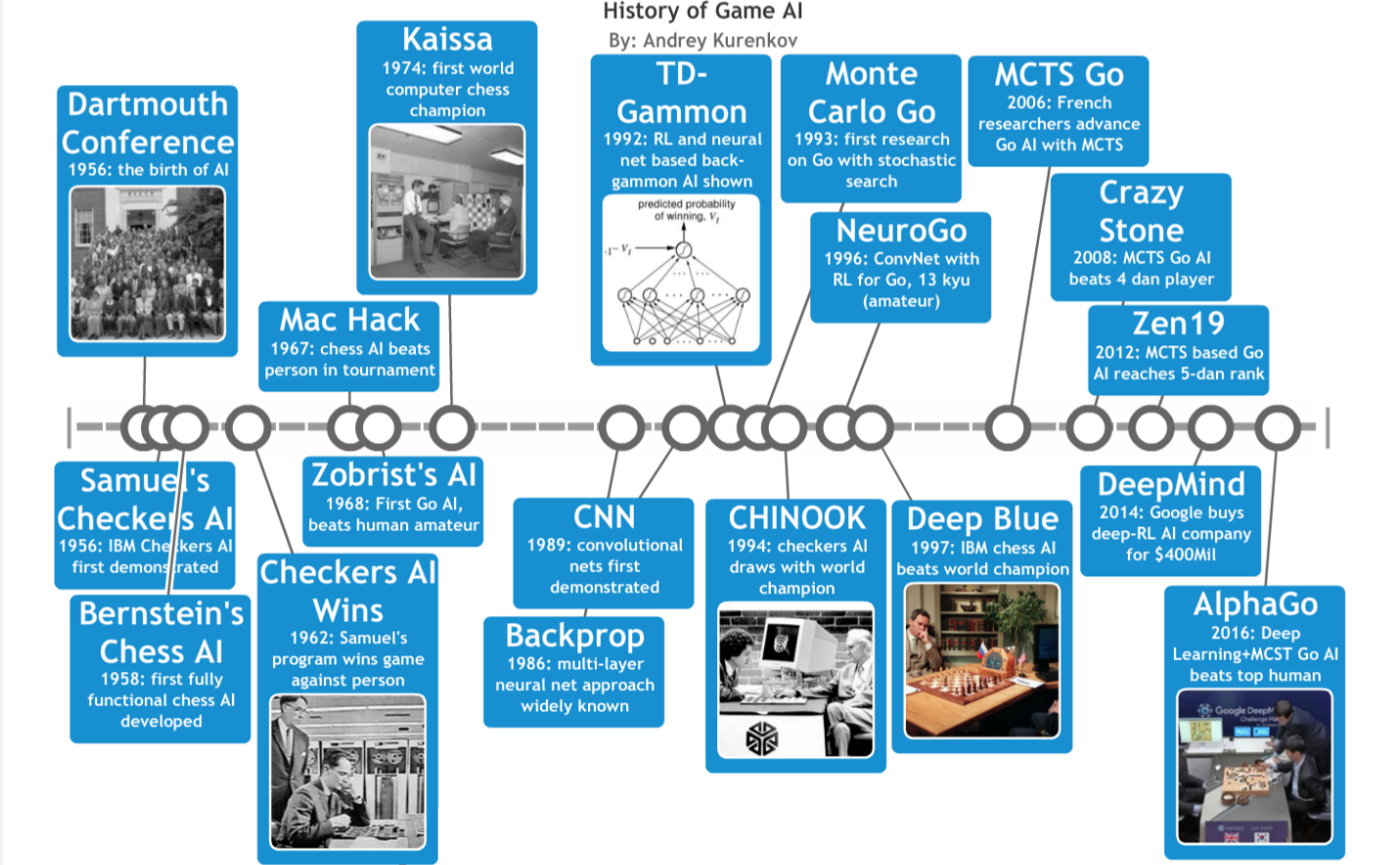

This is the third and final part of ‘A Brief History of Game AI Up to AlphaGo’. Part 1 is here and part 2 is here. In this part, we shall cover the intellectual innovations necessary to finally achieve strong Go programs, and the final steps beyond those that get us all the way to the present and to AlphaGo.

And Then There Was Go

Although Go playing programs by the late 90s were still far from impressive, this was not due to a lack of people trying. Following Bruce Wilcox’s 70s work on Go programs (mentioned in part 2), numerous people continued to dedicate their time and CPU cycles to implementing better Go programs throughout the 80s and 90s. One of the best programs of the 90s, The Many Faces of Go, achieved 13-kyu (good non-professional) performance. It took 30 thousand lines of code written over a decade by its developer, David Fotland, to implement the many Go-specific components it used on top of traditional alpha-beta search1. The combination of a larger branching factor, longer games, and trickier-to-evaluate board positions rendered Go resistant to the techniques that by this time were achieving master-level Chess play. The so-called “knowledge-based” approach of Many Faces of Go (encoding many human-designed strategies into the program) worked, but by the 2000s hit a point of diminishing returns. Traditional techniques were simply not enough.

Fortunately, another family of techniques did exist — Monte Carlo algorithms. The general idea of Monte Carlo algorithms is to simulate a process, usually with some randomness thrown in, in order to statistically get a good approximation of some value that is very hard to calculate directly. For instance, simulated annealing is a classic optimization technique for finding the optimal parameters for some function. It boils down to starting with some random values and semi-randomly changing them to gradually get more optimal values, as shown in the graphic below. If this is done for long enough, it turns out a solution close to the optimal one can most likely be found with much less computation than the actually optimal one would have taken to find.

1993

Monte Carlo techniques had been applied to games of chance such as Blackjack since the 70s, but they were not suggested for Go until 1993 with Bernd Brügmann’s “Monte Carlo Go” 2. The idea he presented was suspiciously simple: Instead of implementing a complex evaluation function and executing typical tree search, have a program just simulate playing many random games (using a version of simulated annealing) and pick the move that leads to the best outcome on average. Remember, the whole reason for evaluation functions is to search only a few moves ahead and not until the end of the game, since the number of possible ways to get to the end is far too immense to thoroughly explore. But, this does not work well for Go since evaluation functions are harder to write for it and typically take much longer to compute than for Chess. So, it turns out that a great alternative is to use that computation time to randomly play out only a subset of possible games (typically described as doing many rollouts), and then evaluate moves based on just counting victories and losses. Despite being radically simple (having little more than the rules of Go), Brügmann’s implementation of the idea showed decent beginner-level play not too far from the vastly more complex Many Faces of Go.

Although it was a novel approach that showed promise for overcoming the problems that stumped traditional Go AI, Brügmann’s work was initially not taken seriously. It was not until the 2000s that a group in Paris made up of Bruno Bouzy, Tristan Cazenave, and Bernard Helmstetter started seriously exploring the potential of Monte Carlo techniques for Go through multiple papers and programs3456. Though they simplified and expanded upon the Brügmann approach (stripping out simulated annealing and adding some heuristics and pruning), their programs were still inferior to the strongest standard tree search ones such as GNU Go. However this lasted only a few years, until several milestone achievements in 2006:

- Rémi Coulom further improved on the use of Monte Carlo evaluation with tree search, and coined the term Monte-Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)7. His program CrazyStone won that year’s KGS computer-Go tournament for the small 9x9 variant of Go, beating other programs such as NeuroGo and GNU Go and thus proving the potential of MCTS.

- Levente Kocsis and Csaba Szepesvári developed the UCT (Upper Confidence Bounds for Trees) algorithm 8. This algorithm solves the choice between exploitation (simulating already good-looking moves to get a better estimate of how good they are) and exploration (trying new or bad-looking moves to try to get something better) in MCTS. The same tradeoff has long been studied in Computer Science in the form of the multi-arm bandit problem, and UCT was a modification of a theoretically-sound Upper Confidence Bounds formula developed for that problem a few years prior.

- Lastly, Sylvain Gelly et al. combined MCTS with UCT as well as the older ideas of local pattern matching and tree pruning9. Their program, MoGo, quickly surpassed CrazyStone and became the best computer Go AI.

2006

The rapid success of CrazyStone and MoGo was impressive enough, but what happened next was truly groundbreaking. In 2008, MoGo beat professional 8 dan player Kim Myungwan in 19x19 Go. Granted, Myungwan was playing with a large handicap and MoGo was running on an 800-node supercomputer, but the feat was nevertheless historic, given that previous Go programs could at best beat highly-ranked amateurs with large handicaps. In the same year, CrazyStone defeated professional Japanese 4 dan player Kaori Aoba with a smaller handicap while running on a normal PC10. And so on it went, with faster computers and various tweaks to MCTS making Go programs rapidly become much, much better.

2012

By 2012, Go programs got good enough for an amateur player to write a post titled “Computers are very good at the game of Go”. The post highlighted the fact that the standout program at the time, Zen19, had improved from a 1 dan ranking (entry-level master) to 5 dan (higher-level master) in the span of 4 years. This is a big deal:

“To put the 5-dan rank in perspective: amongst the players who played American Go Association rated games in 2011, there were only 105 players that are 6-dan and above. This suggests that there are only around 100 active tournament players in the US who are significantly stronger than Zen19. I’m sure I’ll never become that strong myself.”

Still, Go programs were only beating lower-level professionals, and only with significant handicaps. A revolutionary idea — Monte Carlo Tree Search — enabled the ability to brute-force good Go play, and solved the ‘type A’ (smart use of brute-force) strategy part of the problem. It accomplished roughly the same feat as alpha-beta search for Chess programs, but worked better for Go because it replaced the human-implemented evaluation functions component with many random rollouts of the game that were easy to do fast and parallelize to multiple processing cores. But in order to go up against the best humans at, ‘type B’ intelligence (emulation of human-like learned instincts) would also be needed. That would soon be developed, but it would require a second and wholly different revolution - deep learning.

Go AIs Ascend to Divinity with Deep Learning

1994

To understand the revolution of deep learning, we must revisit the 90s. We previously covered the success of Neurogammon, a backgammon program powered by neural nets and supervised learning, as well as TD-Gammon, its successor that was also powered by neural nets but based on reinforcement learning. These programs demonstrated that machine learning was a viable alternative to the knowledge-based approach of hand-coding complex strategies. Indeed, there was an attempt to to apply the approach behind TD-Gammon to Go with 1994’s “Temporal difference learning of position evaluation in the game of Go”11 by Nicol N. Schraudolph, Peter Dayan, and Terrence J. Sejnowski.

Schraudolph et al. noted that efforts to make a Go AI with supervised learning (like Neurogammon) were hindered by the difficulty of generating enough examples of scored Go boards. So they suggested an approach similar to TD-Gammon — training a neural net to evaluate a given board position though playing itself and other programs. However, the team found that using a plain neural net as in TD-Gammon was inefficient, since it did not capture the fact that many patterns on Go boards can be rotated or moved around and still hold the same significance. So they used a convolutional neural net (CNN), a type of neural net constrained to perform the same computation for different parts of the input. Typically, the constraint is to apply the same processing to small patches all over the input, and then have some number of additional layers of looking for specific combinations of patterns, and then eventually use those combinations to compute the overall output. The CNN in Schraudolph et al’s work was simpler, but helped their result by exploiting rotational, reflectional, and color inversion symmetries in Go.

Though this approach could potentially learn to intuitively ‘see’ the value of a Go position (as Zobrist sought to achieve in the 60s), neither the computer power nor the understanding of neural nets were sufficient to make this effective in 1994. In fact, a large wave of hype for neural nets in general died out in the mid 90s as limited computing power and missing algorithmic insights led to underwhelming results. So, the CNN-based program could only beat Many Faces of Go at a low level, and was therefore not even close to good human players.

2006

Neural nets were viewed unfavorably well into the 2000s, while other machine learning methods gained favor and Go programs failed to get much better. The history here is not exact, but a paper titled “A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets”12 is often credited with rekindling interest in neural nets by suggesting an approach for successfully training “deep” neural nets with many layers of computing units. This was the start of what would become the huge phenomenon of deep learning (which is just a term for large neural nets with many layers). In a wonderful historic coincidence, this paper was published in 2006 — the same year as all those MCTS papers!

Deep neural nets continued to gain attention in the following years, and by 2009 achieved record-setting results in speech recognition. Besides algorithmic improvements, their resurgence was in large part due to the availability of large amounts of training data and the use of the massively parallel computational capabilities of GPUs - both things that did not really exist in the 90s. Larger neural nets were trained with more data and more layers, more quickly than before thanks to modern hardware, and benchmark after broken benchmark showed this to be a powerful methodology. But the event that really set off a huge wave of research and investment in deep learning was the ILSVRC (ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge) 2012 computer vision competition. A CNN-based submission performed far, far better than the next-best entry, surpassing the record on that competition’s ImageNet benchmark problem. This, the first and only CNN entry in that competition, was an undisputed sign that deep learning was a big deal. Now, almost all entries to the competition use CNNs.

2012

Up to this point, deep learning was largely applied to supervised learning tasks unrelated to game-playing, such as outputting the right category for a given image or recognizing human speech. But in 2013, a company called DeepMind made a big splash with the publication of “Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning”13. Yep, they trained a neural net to play Atari games. More specifically, they presented a new approach to doing reinforcement learning with deep neural nets, which was largely abandoned as a research direction since the failure of TD-Gammon’s approach to work for other games. With just the input of the pixels you or I would see on screen, and the game’s score, their Deep Q-Networks (named after Q-learning, the basis for their algorithm) learned to play Breakout, Pong, and more. It bested all other reinforcement learning schemes, and in some cases humans as well!

2014

This Atari work was a great innovation in AI research, so much so that in 2014 Google payed $400 million to acquire DeepMind. But I digress - as with IBM’s 2011 win in Jeopardy with Watson, this Atari feat is not directly relevant to the history of AI for chess-like board games, so let’s get back to that. Since the 90s, there were several more papers on learning to predict moves or to evaluate positions in Go with machine learning141516, but up to this point none really used large and deep neural nets. That changed in 2014, when two groups independently trained large CNNs to predict, with great accuracy, what move expert Go players would make in a given position.

The first to publish were Christopher Clark and Amos Storkey at the University of Edinburgh, on December 10th of 2014 with “Teaching Deep Convolutional Neural Networks to Play Go”17. Unlike the DeepMind Atari AI, here the researchers did purely supervised learning: Using two datasets of 16.5 million move-position pairs from human-played games, they trained a neural net to produce the probability of a human Go player making each possible move from a given position. Their deep CNN surpassed all prior results on move prediction for both datasets, and even defeated the conventionally-implemented GNU Go 85% of the time. Prior research on move prediction with weaker accuracy could never achieve better play than GNU Go, but this research showed that it could be done by just playing the moves deemed likely to be the choice of a skilled player by a neural net trained on lots of data!

It’s important to understand that the neural net had no prior knowledge of Go before being trained with the data - it did not know the rules of the game and did not simulate playing Go for its move selection. So, you could say it was playing purely by ‘intuition’ for good moves, based on the data it had seen in training. Therefore it is hugely impressive that Clark et al’s neural net was able to beat a program specifically written to play Go well, but also not surprising it alone could not beat the stronger existing MCTS-based Go programs (which by that point played as well as very skilled people). The researchers concluded by suggesting the ‘intuition’ of machine-learned move prediction could be combined with brute-force MCTS move evaluation to make a much stronger Go AI than had ever existed:

“Our networks are state of the art at move prediction, despite not using the previous moves as input, and can play with an impressive amount of skill even though future positions are not explicitly examined. … The most obvious next step is to integrate a DCNN into a full fledged Go playing system. For example, a DCNN could be run on a GPU in parallel with a MCTS Go program and be used to provide high quality priors for what the strongest moves to consider are. Such a system would both be the first to bring sophisticated pattern recognitions abilities to playing Go, and have a strong potential ability to surpass current computer Go programs.”

Within a mere two weeks of the publication of Clark et al’s work, a second paper was released describing research with precisely the same ambitions, by Chris J. Maddison (University of Toronto), Ilya Sutskever (Google), and Aja Huang and David Silver (DeepMind, now also part of Google)18. They trained a larger, deeper CNN and achieved even more impressive prediction results plus the ability to beat GNU Go a whopping 97% of the time. Still, when faced with MCTS programs operating at full brute force capacity — 100,000 rollouts per move — the deep neural net won only 10% of the time. As with the first paper, it was suggested that neural nets could be used together with MCTS, that the former could serve as ‘intuition’ to quickly identify potentially good moves, and the latter could serve as ‘reasoning’ to more accurately evaluate how good those moves really are. This team went further by implementing a prototype program that did just that, and showed it could beat their lone neural net 87% of the time. They concluded:

“We have provided a preliminary proof-of-concept that MCTS and deep neural networks may be combined effectively. It appears that we now have two core elements that scale effectively with increased computational resource: scalable planning, using Monte-Carlo search; and scalable evaluation functions, using deep neural networks. In the future, as parallel computation units such as GPUs continue to increase in performance, we believe that this trajectory of research will lead to considerably stronger programs than are currently possible.”

2016

They did not just believe in that trajectory of research — they pursued it. And just shy of a year later, their belief was proven right. In January of 2016, a paper in the prestigious publication Nature by these four authors and some sixteen more (all from DeepMind or Google) announced the development of AlphaGo, the first Go AI to beat a high ranked professional player without any handicaps19. Specifically, they reported having beaten Fan Hui, a European Go champion, in 5 out of 5 no-handicap games.

How did they build a Go AI this good? With a small battalion of incredibly intelligent people working to achieve quite a list of innovative ideas:

- First, they created a much better neural net for predicting the best move for a given position. They did this by starting with supervised learning from a dataset of 30 million position-move pairs from games played by people (aided by some simple Go features), and then improving this neural net with reinforcement learning (making it play against older versions of itself to learn to get better, TD-Gammon style). This singular neural net — the policy network — could by itself beat the best MCTS Go programs 85% of the time, a huge leap from the 10% that was achieved before. But they did not stop there.

- A natural next step to get even better performance was to add MCTS into the mix, but the policy neural net is far too slow to be evaluated continually for each move of the tens of thousands of game rollouts typically done with MCTS. So, the supervised learning data was also used to train a second network that is much faster to evaluate - the rollout network. The full policy network is only ever used once to get an initial estimate on how good a move is, and then the much faster rollout policy is used in choosing the many more moves needed to get to an end of the game in an MCTS rollout. This makes the move selections in simulation better than random but fast enough to have the benefits of MCTS. These two components together with MCTS already made for a far better Go AI than has every been achieved, but there was a third trick that really pushed AlphaGo into the highest ranks of human skill.

- A huge part of why MCTS works so well for Go is that it removes the need to write evaluation functions for positions in Go, which is hard. Well, if we can train a neural net to predict what good moves are, it’s not hard to imagine we could also train a neural net to evaluate a Go position. And that is precisely why this group did: They used the already-trained high quality policy network to generate a dataset of positions and final outcomes in that game, and trained a value network that evaluated a position based on the overall probability of winning the game from that position. So the policy net suggests promising moves to evaluate, which is then done through a combination of MCTS rollouts (using the rollout net) and the value network prediction, which together turn out to work significantly better than either by itself.

- To top everything off, all of this was implemented in a hugely scalable manner that can and did leverage hardware that easily surpassed anything that was used for Go play in the past. AlphaGo used 40 search threads running on 48 CPUs, with 8 GPUs for neural net computations being done in parallel. And that’s just one one computer! AlphaGo was also implemented in a distributed version which could run on multiple machines, and scale to more than a thousand CPUs and close to 200 GPUs.

(B) And a breakdown of how these networks are used in conjunction with MCTS. I recommend this technical summary for more detail. (Source: also from the Nature Paper, with modified annotations by Shane (Seungwhan) Moon)

Besides training a state-of-the-art move predictor through a combination of supervised and reinforcement learning, probably the most novel aspect of AlphaGo is the strong integration of machine-learned intelligence with MCTS. Whereas the 2014 paper only contained a very preliminary combination of MCTS with a CNN, and before that MCTS programs contained at most modest integrations with supervised learning, AlphaGo gets its strength from being a well designed hybrid AI approach that is run on modern-day supercomputer hardware. Put simply, AlphaGo is a huge successful synthesis of multiple prior effective approaches that is far better than any of those individual elements alone. At least one other team, Yuandong Tian and Yan Zhu from Facebook, explored the same MCTS+deep learning idea in the same timeframe and likewise achieved impressive results 20. But the Google team definitely invested much more effort and resources into AlphaGo, and that ultimately paid off when it achieved a historic milestone for AI.

AlphaGo = Deep Supervised Learning (with domain-specific features) + Deep Reinforcement Learning + Monte Carlo Tree Search + Hugely parallel processing

And now, finally, we are back to where we began: Just a few months after the announcement of AlphaGo’s existence, it faced off against one of the best living Go players and decidedly won. This will perhaps go down as a historic moment not just for the field of AI, but for the whole history of human invention and ingenuity. I think it is fascinating to see how we can trace the intellectual efforts to accomplish this decades back, with every idea used to build AlphaGo being a refinement on one that came before it, and see that (as always in science and engineering) credit here is due to both a large team at Google and dozens of people that made their work possible. Now, what of the future?

Epilogue: AI After AlphaGo

Congratulations, dear reader, you made it. I am impressed and appreciative that you got to this point. With this full history well trodden, I hope that my secret motivation in writing this clear — to show that AlphaGo is not some scary incomprehensible AI program, but really a quite reasonable feat of human research and engineering. And also to note that Go, ultimately, is still a strategic board game. Yes, it is a game for which it is hugely challenging to make good computer programs. But, in being a game, it also possesses multiple nice properties that make AlphaGo possible, as shown in the above Venn Diagram.

There are many, many problems still in the realms of AI that are outside the intersection of those nice properties. To name just a few: playing Starcraft or Soccer, human-like conversation, (fully) autonomous driving. This is an incredible time for AI research, as we are starting to see these problems being tackled by well funded researchers like the ones at Google. In fact, I think it is appropriate to end with this quote from the AlphaGo team itself:

“But as they say about Go in Korean: “Don’t be arrogant when you win or you’ll lose your luck.” This is just one small, albeit significant, step along the way to making machines smart. We’ve demonstrated that our cutting edge deep reinforcement learning techniques can be used to make strong Go and Atari players. Deep neural networks are already used at Google for specific tasks — like image recognition, speech recognition, and Search ranking. However, we’re still a long way from a machine that can learn to flexibly perform the full range of intellectual tasks a human can — the hallmark of true artificial general intelligence.

With this tournament, we wanted to test the limits of AlphaGo. The genius of Lee Sedol did that brilliantly — and we’ll spend the next few weeks studying the games he and AlphaGo played in detail. And because the machine learning methods we’ve used in AlphaGo are general purpose, we hope to apply some of these techniques to other challenges in the future. Game on!”

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to Abi See and Pavel Komarov for helping to edit this.

References

-

David Fotland (1993). Knowledge representation in the Many Faces of Go. ↩

-

Brügmann, B. (1993). Monte carlo go (Vol. 44). Syracuse, NY: Technical report, Physics Department, Syracuse University. ↩

-

Bouzy, B., & Helmstetter, B. (2004). Monte-carlo go developments. In Advances in computer games (pp. 159-174). Springer US. ↩

-

Cazenave, T., & Helmstetter, B. (2005). Combining Tactical Search and Monte-Carlo in the Game of Go. CIG, 5, 171-175. ↩

-

Bouzy, B. (2005). Associating domain-dependent knowledge and Monte Carlo approaches within a Go program. Information Sciences, 175(4), 247-257. ↩

-

Coulom, R. (2009, January). The Monte-Carlo Revolution in Go. In The Japanese-French Frontiers of Science Symposium (JFFoS 2008), Roscoff, France. ↩

-

Coulom, R. (2006). Efficient selectivity and backup operators in Monte-Carlo tree search. In Computers and games (pp. 72-83). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ↩

-

Kocsis, L., & Szepesvári, C. (2006). Bandit based monte-carlo planning. In Machine Learning: ECML 2006 (pp. 282-293). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ↩

-

Gelly, S., Wang, Y., Teytaud, O., Patterns, M. U., & Tao, P. (2006). Modification of UCT with patterns in Monte-Carlo Go. Technical Report RR-6062, 32, 30-56. ↩

-

History of Go-playing programs. http://www.britgo.org/computergo/history ↩

-

Schraudolph, N. N., Dayan, P., & Sejnowski, T. J. (1994). Temporal difference learning of position evaluation in the game of Go. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 817-817. ↩

-

Hinton, G. E., Osindero, S., & Teh, Y. W. (2006). A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural computation, 18(7), 1527-1554. ↩

-

Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Graves, A., Antonoglou, I., Wierstra, D., & Riedmiller, M. (2013). Playing atari with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.5602. ↩

-

Sutskever, I., & Nair, V. (2008). Mimicking Go experts with convolutional neural networks. In Artificial Neural Networks-ICANN 2008 (pp. 101-110). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ↩

-

Stern, D., Herbrich, R., & Graepel, T. (2006, June). Bayesian pattern ranking for move prediction in the game of Go. In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning (pp. 873-880). ACM. ↩

-

Wu, L., & Baldi, P. F. (2006). A scalable machine learning approach to go. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 1521-1528). ↩

-

Clark, C., & Storkey, A. (2014). Teaching deep convolutional neural networks to play go. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.3409. ↩

-

Maddison, C. J., Huang, A., Sutskever, I., & Silver, D. (2014). Move evaluation in go using deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6564. ↩

-

David Silver, Aja Huang, Christopher J. Maddison, Arthur Guez, Laurent Sifre, George van den Driessche, Julian Schrittwieser, Ioannis Antonoglou, Veda Panneershelvam, Marc Lanctot, Sander Dieleman, Dominik Grewe, John Nham, Nal Kalchbrenner, Ilya Sutskever, Timothy Lillicrap, Madeleine Leach, Koray Kavukcuoglu, Thore Graepel & Demis Hassabis (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529, 484-503. ↩

-

Tian, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2015). Better Computer Go Player with Neural Network and Long-term Prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.06410. ↩

Previous Post | Next Post

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.